Surgical Therapies for Stress Incontinence

Should I have a surgery to treat Stress Incontinence?

Unlike more conservative therapies such as pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises, surgery to treat Stress Incontinence (SUI) carries certain risks. Because of these risks, the consideration of surgery should always take into account how bothersome your symptoms are and how much they affect your life. The amount and frequency of any stress leakage can be useful in determining how much improvement you can expect from a procedure. If you have minimally bothersome symptoms, you are less likely to see much of a benefit from surgery and may be unwilling to accept even the relatively low risks of surgical therapy. If you have symptoms that have a greater effect on your lifestyle, you are more likely to see substantial benefit from surgery and may be more willing to accept any risks.

Another questions to ask your doctor is whether you have any special factors that place you at increased risk for complications from stress incontinence surgery. There are many health issues that can make incontinence surgery more risky, but some common factors include neurologic conditions that affect your bladder, difficulty emptying your bladder, and diseases or medications that affect wound healing. Even someone with relatively bothersome symptoms may want to consider alternatives to surgical therapy for SUI if serious risk factors are present.

What are the alternatives to surgery for SUI?

Urinary incontinence is a quality of life issue, meaning your opinion about your symptoms is what is really important. You may decide that your Stress Incontinence (SUI) is simply not bothersome enough for any therapy. And that is OK. You shouldn’t be fearful of treatments for incontinence but you also should not feel that you have to choose any therapy if you don’t want to.

Pelvic floor exercises can be an effective way of treating Stress Incontinence. This may be the most appropriate therapy for mild or minimally bothersome SUI. Pelvic floor exercises can be done on your own with guidance from your health provider or you may want to meet with a specialized provider called a Pelvic Floor Physical Therapist. They are specially trained physical therapists who can help to increase the effectiveness of pelvic floor exercises. It is important to note that successful pelvic floor exercise requires dedication on the part of the patient. You will generally need to continue performing the exercises regularly to continue seeing benefits.

Finally, there are devices that can be placed into the vagina, called incontinence pessaries, that compress the urethra, and can help control stress leakage. These can be fitted by your health provider or even purchased over the counter. They do have to be changed or removed regularly so this can result in some inconvenience. However, they carry few risks and are well-tolerated by some women.

Sling Surgery for Stress Incontinence

What are the types of slings used for Stress Incontinence?

The two main types of slings used to treat Stress Incontinence (SUI) are synthetic slings and autologous fascial slings. Synthetic slings are by far the most common type of sling used today. If you are discussing a sling procedure with your doctor or if you know someone who had a sling surgery for incontinence, odds are that it was a synthetic sling. Autologous fascial slings are most often used in special circumstances when a synthetic sling may not be advised (such as in a repeat incontinence surgery).

What Causes SUI

SUI is commonly associated with a lack of support of the urine tube you urinate through (called the urethra). This lack of support can result from pregnancy, childbirth, advancing age, or even the types of support tissues you inherit. This can lead to excessive up and down movement of the urethra called urethral hypermobility. Your doctor may have looked for this on a vaginal exam and it is thought that this movement contributes to SUI. Slings work by limiting this movement. They stop urethral hypermobility. That helps with stress incontinence.

Slings are usually described by where they pass on their way under the urethra. There are some differences among them but none of these types of synthetic sling have generally been found to work better or have fewer complications overall. If you have decided on a synthetic sling, all of these options are likely reasonable choices for you. It may even be true that the best sling for you is the one that your doctor has the most experience with. Therefore, it is helpful to discuss your doctor’s experience before making your decision. Because this is what I specialize in, I happen to have enough experience with all of the sling types that I usually let other patient factors guide our decisions on sling choice.

Retropubic Slings

Retropubic slings pass behind (retro) the pubic bone (pubic) on their way under the urethra to prevent it from moving excessively. They provide good support in this way and have success rates ranging from 50-87% (depending on how strictly you define success). They may either be passed from above the pubic bone down toward the urethra or upwards from the urethra toward the pubic bone. There is no clear preference for either method of passing the sling. In my practice, I use a sling with an above to below passage. Retropubic slings have been used for well over 20 years and are a common, effective and generally safe incontinence surgery. I tend to favor retropubic slings in women who leak with lower pressures, are also having repair of vaginal prolapse, or are having a second sling placed after failure of a first (this is uncommon).

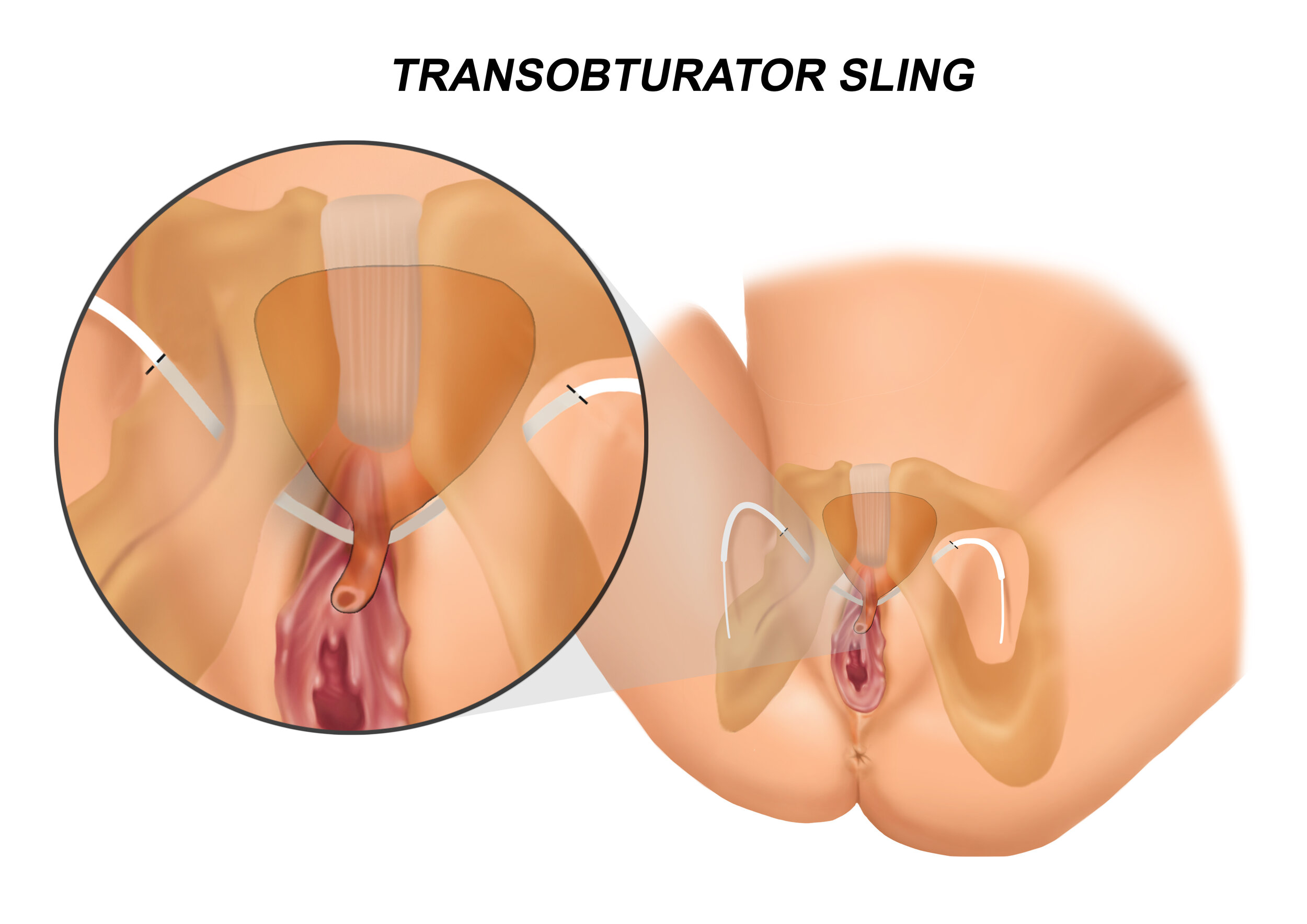

Transobturator Slings

Transobturator slings are placed through (trans) a passage in the pelvis (obturator) and then pass beneath the urethra to provide support, similar to a retropubic sling. Success rates are nearly identical to retropubic slings, 43-92%, again depending on how strictly you define success. Satisfaction rates are generally above 80-90% with both retropubic and transobturator slings. Just as retropubic slings can be passed from above or below, transobturator slings can be passed either from outside the pelvis toward the urethra or from the urethra outside toward the pelvis. As with retropubic slings, how you pass the sling does not appear to have an overall impact on complications or success. In my patients, I pass from the outside toward the urethra. Transobturator slings may have an advantage of avoiding passage near enough to the bladder or intestines to cause an injury. However, these types of problems are rare enough that most studies do not show a difference in complication rates. I tend to prefer transobturator slings in most women unless there is another factor such as those noted above for retropubic slings or those noted below for autologous fascial slings.

Single-Incision Slings

Single-incision slings were developed to be similar to transobturator slings but without passing around the pelvic bones. This may make them simpler to place. More recent studies of these slings show that they may be as effective as transobturator and retropubic slings. However, they have been used for a shorter time so it may be a while before we have better long-term comparisons. These are still effective and safe types of slings to be used and may have some advantages in women who would have difficulty in passing a transobturator or retropubic sling. Single-incision slings may reduce the leg pain that can be seen in some transobturator sling patients. Much like transobturator slings, there is a decreased risk of injury to the bladder or intestines.

Autologous Fascial Slings

Autologous fascial slings (also called pubovaginal slings and abbreviated PVS) are a very different sling compared with the synthetic slings. First, they are not manufactured but instead are crafted, at the time of surgery, from tissue harvested from the patient. Most of your muscles are covered with a strong covering called fascia. A strip of this fascia is cut away from the muscle (no portion of the muscle is removed) and this strip is used as the sling. The muscles that can be used are the lower abdominal muscles (rectus fascia) or the covering of the outside of the thigh muscle, just above the knee (tensor fascia lata). I use both of these but tend to prefer the tensor fascia lata as I think that patients recover a bit more quickly from this harvest.

Autologous fascial slings (or pubovaginal slings) also differ from synthetic slings in terms of where they are placed. I often hear patients refer to synthetic slings as bladder slings. However, synthetic slings are actually placed in the middle of the urethra, well away from the bladder. Pubovaginal slings are placed at the bladder neck, the location where the bladder and the urethra merge. These are closer to being “bladder slings” though I still use the term bladder neck slings to try be more accurate.

Because they are placed at the bladder neck instead of the middle of the urethra, pubovaginal slings work differently from synthetic slings in important ways - some good and some bad. Synthetic slings stop the urethra from moving and this helps the muscles that keep you from leaking (including the external urethral sphincter) to work more normally. But pubovaginal slings function more by helping to close the bladder neck instead of preventing the urethra from moving up and down. In patients who have severe damage to the sphincter muscles, they appear to perform better. But by compressing the bladder neck, they are more likely to make it difficult for you to urinate afterward. The rates of not being able to urinate immediately after surgery are much higher in pubovaginal slings. Fortunately, this often resolves in the weeks after the surgery, but can be quite distressing to patients during that time. There is also usually pain where we have to remove the fascia either at the leg or the stomach muscles. This pain is usually more than you would see with a synthetic sling surgery. Because of these factors, I do not recommend these types of slings to most of my patients. I use fascial slings commonly but in very specific circumstances. This includes patients who have failed a previous synthetic sling surgery, who have stress incontinence but little or no movement of their urethra, who leak at extremely low levels of exertion, or who have a complicated history (like pelvic radiation or a urethral injury).

What are the risks of synthetic slings?

The most common side effect of synthetic sling surgery is urinary frequency and urgency that begins after surgery. This can be difficult to identify because many women who have stress incontinence also have urgency incontinence. But there are women who develop new urgency symptoms or have worsening of existing urgency after sling surgery. This may be due to irritation from the sling or may be due to compression of the urethra.

Problems Urinating

Occasionally, the sling can compress the urethra enough to make it very difficult to empty your bladder. This occurs, in my experience 1-3%, of the time and may even require that the sling be cut to relieve the compression. If your sling becomes too tight, you may notice that it is very hard to urinate. You may be able to urinate well but could notice new frequent and urgent urination as above. This is usually seen in the weeks to months immediately after sling placement and is an important reason to follow up after sling surgery.

Sling Exposure

Since slings are made of synthetic material, they must be well-covered by vaginal tissue. If a portion of the sling is exposed in the vagina this can lead to infection or pain. Sometimes, if the area of exposure is very small (<1 cm) we can help the vaginal tissue heal over the sling by using estrogen cream. However, if the exposure is larger, this often requires the removal of that portion or all of the sling. Removing a portion of the sling can result in a return of stress incontinence. I see vaginal exposure in less than 1% of the sling surgeries I have performed.

Pelvic Pain

After any incontinence surgery, patients may report pelvic pain, including vaginal pain. This pelvic pain sometimes occurs on its own but can also be seen with intercourse. In some cases, the vaginal pain can be traced to a sling that is exposed or is too tight and the exposed portion can be removed or the sling can be cut to release the tension. However, it is possible for patients with a sling that is neither too tight nor exposed to still have pelvic pain after sling surgery. When I see this, there is often dysfunction of the pelvic muscles and pelvic floor physical therapy can be very useful. It is likely that pelvic pain is a risk of nearly all incontinence procedures, rather than being unique to sling surgeries.

Perforation

An uncommon complication of slings is injury to the bladder during passage of the sling. However, during sling surgery, a small scope can be placed in the bladder to check for any injury to the bladder. This reduces the risk of sling passage through the bladder, though it is difficult to say that it eliminates it entirely. Another complication of retropubic and pubovaginal slings is damage to the intestines. This is a very serious complication that is fortunately very rare.

How safe are synthetic slings for Stress Incontinence?

Synthetic mid-urethral slings used to treat Stress Incontinence (SUI) have been widely used in the United States for over 20 years. This provides us with a long history to evaluate both short-term and long-term improvement as well as risks of complications. We don't have to wonder how slings might change in the body over the next 20 years because we can see the results in patients who have had them for the last 20 years. Synthetic slings are made of a material called polypropylene that is used in other surgical specialties for things like hernia repair and transplant surgery. This material has been used for these purposes for over 50 years.

How Slings Are Different

Using polypropylene for different surgical purposes results in different risks. One use of polypropylene mesh has been to repair vaginal hernias, called pelvic prolapse. Using synthetic mesh to repair prolapse is very different from using it to treat incontinence. How is it different? In pelvic prolapse, the wall of the vagina is pushed out by the bladder, the intestines, or the uterus. Using mesh to repair this "pushed out" vaginal wall means using the mesh to pull these tissues back into place. Pulling on tissue means tension. And tension results in very specific risks when using a synthetic material, including higher risks of pain. Stress Incontinence slings are meant to support the urethra but not to place any tension on the tissue. It acts like a net to catch a "falling" urethra (urethral hypermobility) to help with incontinence. It does not have to pull the urethra back into place as with prolapse. Because there should be no tension on the urethra, the risk of pain and damage to the tissues is much different than what we see in mesh used to treat vaginal prolapse. Very different uses mean very different risks.

In April 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration issued an order calling for the elimination of synthetic mesh to repair prolapse through a vaginal incision. This caused considerable confusion for the public regarding synthetic slings used to treat stress incontinence (mid-urethral slings). It doesn’t help that many patients (and doctors, honestly), often incorrectly refer to SUI slings as "bladder slings". This confusion is unfortunate because the FDA decision about synthetic mesh used to treat prolapse had no effect on the use of urethral slings for incontinence. Unfortunately, I'm still asked about this from confused patients every week.

Slings Are Extremely Well Studied

Polypropylene slings that are placed beneath the urethra (under no tension) to treat SUI have been analyzed in over 2,000 publications since the early 1990s. There is simply no other surgical therapy for stress incontinence that has been studied so thoroughly. With this attention over the last 25 years, we have learned that mid-urethral slings are at least as effective as any other SUI surgery and are associated with less pain, shorter time in hospital, and faster return to normal activity. They are considered the gold-standard treatment of stress incontinence today and are by far the most common surgery for SUI.

Slings Are Safe and Effective

This safety and effectiveness is reflected by the FDA statements regarding mid-urethral slings. While the FDA moved to restrict and later remove vaginal prolapse mesh, they have not altered the recommendations on the use of synthetic slings to treat incontinence. While it may be the same material, it is used in a very different way and this matters a lot. For my patients who are concerned about the safety of slings to treat their SUI, I always review the risk factors that are described above. But I note that the alternative procedures have similar risks, sometimes with less effectiveness. I ask them to consider their concerns about risk versus the amount of improvement they expect to see and how bothered they are by their incontinence. This balance helps them to make an informed decision. While some may choose to avoid surgery, many feel that the benefits outweigh the risks for them.

What are the alternatives to synthetic sling surgery?

It’s important to stress that surgical therapies are not the only treatment for Stress Incontinence (SUI). Pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises can be effective for some women and should be considered first-line therapy. Some women may also choose to use vaginal incontinence pessaries, which compress the urethra to prevent SUI. However, pelvic exercises and vaginal inserts are not always successful or tolerated and many women feel that surgical therapies are more appropriate for their condition. So, are there surgical alternatives to synthetic slings?

Pubovaginal Slings

One alternative for people who are resistant to a synthetic sling is using an autologous fascial sling. As described above, these slings are crafted from the tissue covering your leg or abdominal muscles (fascia) obtained at the time of surgery. The sling is then passed beneath the bladder neck to provide support and some compression. While they do not contain any synthetic materials, fascial slings do require two additional incisions: one to obtain the sling and another to tie the arms of the sling together. There is usually pain and scar at the site of these incisions, especially the location to obtain the fascia for the sling. I use these slings frequently but almost always in patients with complicating factors such as extreme weakness of the sphincter muscles, previous surgeries, pelvic radiation or injury to the area where the sling will be located.

Retropubic Suspensions

A very different type of incontinence surgery involves “suspending” the urethra and bladder neck from the stronger tissues around it. While this uses synthetic sutures, it does not use a synthetic mesh sling. Limited studies show this may as effective as synthetic slings in the short-term, though not as effective as fascial slings. One concern is the incisions used to perform the procedure with as many as 20% of patients reporting wound issues. Though retropubic suspensions are still considered an acceptable treatment for SUI, this type of procedure has mostly been replaced by synthetic slings.

Urethral Bulking

A final surgical treatment of SUI injects a small amount of material into the urethral wall at the location of the urethral sphincter muscles. This bulking material partially closes the urethra and makes it easier for the sphincter muscles to stop stress leakage. The biggest advantage of bulking injections is that they can be done through a small scope inserted into the urethra, often with minimal sedation. This can be an advantage for patients who are at increased risk from a more extensive surgery. Repeated injections to maintain improvement are frequently needed and the long-term success of bulking therapy is unclear. I primarily use bulking procedures in patients who would be at significant risk from a more extensive surgery. Another use I have found is in patients who are mostly improved with a sling surgery but have a small amount of continued SUI that is bothersome.

While alternative surgeries to synthetic slings do exist, it is clear that synthetic slings have an important role in the treatment of SUI by providing a very effective treatment that is generally safe. Patients with bothersome SUI who have not responded to pelvic exercises and who do not have any complicating factors can be reassured that a synthetic sling is an appropriate therapy.

What kind of evaluation do I need if I’m thinking of sling surgery?

It is important enough to repeat that evaluating patients before sling surgery means getting a good history about their incontinence and other medical issues. It is so crucial to understand enough about your incontinence so that you can determine whether a sling surgery is likely to provide benefit. I commonly see patients for a second opinion in my practice after a “failed” sling who appear to have had a sling placed for the wrong kind of incontinence. It is critical to assess whether patients have Stress Incontinence, Urgency Incontinence, or both as well as how bothersome each type of incontinence may be. Synthetic slings treat stress not urgency incontinence. A diary tracking frequency of urination and leakage is very useful in assessing the contribution of different types of incontinence. This is also a time to learn about any previous surgeries or medical issues that can affect surgical decisions. A physical exam that looks specifically at the urethra and how much it moves, as well as the remaining anatomy of the vagina and bladder, is a necessary part of the evaluation.

Taking a history and performing a physical exam help to determine if any additional testing is necessary. A pressure test of the bladder (urodynamic evaluation) may be performed prior to surgery to obtain a better understanding of the cause of incontinence and how the bladder functions. However, urodynamic testing is probably not strictly necessary in otherwise healthy patients with obvious SUI, who have no complicating factors such a previous incontinence surgery or advanced vaginal prolapse. Occasionally, it may be wise to place a small scope (cystoscopy) inside the bladder prior to incontinence surgery. This is usually not necessary. Blood seen in the urine (either by you or by the lab) or a previous incontinence procedure such as a synthetic sling are the most common reasons to look into the bladder before an incontinence surgery.

What kind of a doctor do I need to see for sling surgery?

Many general urologists and gynecologists have plenty of training and experience in performing synthetic sling surgery. Most of the advancements in sling surgery have been directed at making these procedures simpler and safer. I do not think it is always necessary to seek a specialist such as someone certified in Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) to have a sling surgery. However, there are certain circumstances in which the training and experience of someone who focuses on bladder and pelvic health can be useful.

Patients who have had a prior incontinence procedure and continue with stress incontinence should be carefully evaluated prior to considering sling surgery. The prior incontinence surgery may have resulted in injury to the bladder or urethra, blockage of urine exiting the bladder or excessive scarring of the urethra and sphincter muscles. Any of these factors would make a synthetic sling surgery a poor choice and a more thorough evaluation would always be necessary in these circumstances. It may take someone with a background in Female Pelvic Medicine to identify such issues and to make appropriate recommendations.

Other complicating factors include having a neurologic disorder capable of affecting bladder function or previous pelvic radiation therapy. Both of these issues suggest that a pressure test of the bladder should be performed prior to any sling surgery for incontinence. Again, training and experience in complex bladder and incontinence issues can be very useful in formulating an effective and safe plan under these circumstances.